Regular Expression Cheat Sheet: Collection of Commonly Used Patterns

A compilation of the most frequently used regex patterns and practical examples in web development.

Why Should You Learn Regular Expressions?

Regular expressions (Regex) are like a Swiss Army knife for developers. They seem difficult at first, but once you're familiar with them, you can replace dozens of lines of string processing code with just one line. Regular expressions shine in almost all string-related tasks: email validation, phone number extraction, log parsing, text replacement, and more.

The reason many developers fear regular expressions is that the syntax isn't immediately understandable. Code like /^[a-zA-Z0-9._%+-]+@[a-zA-Z0-9.-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,}$/ looks like a cipher. But once you understand the basic syntax, you can read this pattern logically too. In this article, we'll first explain the core syntax of regular expressions, then break down frequently used patterns in practice one by one.

Understanding Basic Syntax Systematically

Regular expression syntax can be broadly divided into four categories: metacharacters, quantifiers, groups, and anchors.

Metacharacters: Characters with Special Meaning

Metacharacters represent specific character sets or conditions.

| Symbol | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

. | Any character except newline | a.c -> abc, adc, a1c |

\d | Digit (0-9) | \d+ -> 123, 4567 |

\D | Non-digit character | \D+ -> abc, !@# |

\w | Word character (a-z, A-Z, 0-9, _) | \w+ -> hello_123 |

\W | Non-word character | \W -> space, special chars |

\s | Whitespace (space, tab, newline) | \s+ -> multiple spaces |

\S | Non-whitespace character | \S+ -> consecutive words |

Quantifiers: Expressing Repetition

Quantifiers specify how many times the preceding element repeats.

| Symbol | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

* | 0 or more | ab* -> a, ab, abb, abbb |

+ | 1 or more | ab+ -> ab, abb, abbb |

? | 0 or 1 | colou?r -> color, colour |

{n} | Exactly n | \d{4} -> 2025 |

{n,} | n or more | \d{2,} -> 10, 100, 1000 |

{n,m} | Between n and m | \d{2,4} -> 10, 100, 1000 |

Anchors and Boundaries

Anchors match positions, not characters themselves.

| Symbol | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

^ | Start of string | ^Hello -> matches "Hello World" |

$ | End of string | World$ -> matches "Hello World" |

\b | Word boundary | \bcat\b -> matches "cat" only, not "catch" |

\B | Non-word boundary | \Bcat -> cat in "catch" |

Groups and Capture

Using parentheses allows you to group patterns and capture matched parts.

const dateStr = '2025-12-25';

const regex = /(\d{4})-(\d{2})-(\d{2})/;

const match = dateStr.match(regex);

console.log(match[0]); // '2025-12-25' (full match)

console.log(match[1]); // '2025' (first group - year)

console.log(match[2]); // '12' (second group - month)

console.log(match[3]); // '25' (third group - day)

Practical Pattern Collection: Breaking Down Each One

1. Email Validation

The email pattern is a classic regex example. Let's break it down step by step.

const emailRegex = /^[a-zA-Z0-9._%+-]+@[a-zA-Z0-9.-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,}$/;

Pattern breakdown:

^- Start of string[a-zA-Z0-9._%+-]+- Local part (before @): 1 or more alphanumeric, dots, underscores, etc.@- @ symbol (literal)[a-zA-Z0-9.-]+- Domain name: 1 or more alphanumeric, dots, hyphens\.- Dot (needs escaping)[a-zA-Z]{2,}- Top-level domain: 2 or more alphabetic (com, org, museum, etc.)$- End of string

Edge case handling:

This pattern validates most common emails but doesn't fully comply with RFC 5322 standard. For example, emails with quotes like "user name"@example.com won't match. In practice, format validation followed by actual email sending is the most reliable approach.

2. Password Strength Check

To validate complex password rules with regex, use lookahead.

// Minimum 8 chars, uppercase, lowercase, number, special character

const passwordRegex = /^(?=.*[a-z])(?=.*[A-Z])(?=.*\d)(?=.*[@$!%*?&])[A-Za-z\d@$!%*?&]{8,}$/;

Pattern breakdown:

(?=.*[a-z])- Must contain at least 1 lowercase (lookahead)(?=.*[A-Z])- Must contain at least 1 uppercase(?=.*\d)- Must contain at least 1 digit(?=.*[@$!%*?&])- Must contain at least 1 special character[A-Za-z\d@$!%*?&]{8,}- 8 or more allowed characters

Lookahead (?=...) checks if the pattern exists but doesn't consume characters. This allows checking multiple conditions simultaneously.

3. Phone Number Validation

A pattern to validate phone numbers.

const phoneRegex = /^(\+1)?[-.\s]?\(?\d{3}\)?[-.\s]?\d{3}[-.\s]?\d{4}$/;

Pattern breakdown:

(\+1)?- Optional country code[-.\s]?- Optional separator (hyphen, dot, or space)\(?\d{3}\)?- Area code, optionally wrapped in parentheses\d{3}- First 3 digits\d{4}- Last 4 digits

phoneRegex.test('123-456-7890'); // true

phoneRegex.test('(123) 456-7890'); // true

phoneRegex.test('+1 123 456 7890'); // true

4. Name Validation

When validating names, you can use character ranges for different languages.

// English names

const nameRegex = /^[a-zA-Z\s'-]{2,50}$/;

nameRegex.test('John Doe'); // true

nameRegex.test("O'Brien"); // true

nameRegex.test('Mary-Jane'); // true

5. URL Validation

URL patterns need to support various formats, making them complex.

const urlRegex = /^(https?:\/\/)?(www\.)?[\w-]+(\.[a-z]{2,})+([\/\w.-]*)*\/?$/i;

Pattern breakdown:

(https?:\/\/)?- Protocol (http:// or https://) optional(www\.)?- www. optional[\w-]+- Domain name(\.[a-z]{2,})+- TLD like .com, .co.uk (1 or more)([\/\w.-]*)*- Path (optional)\/?$- Optional trailing slashiflag - Case insensitive

6. IPv4 Address Validation

Each octet of an IPv4 address must be in the range 0-255. Expressing this in regex:

const ipv4Regex = /^(?:(?:25[0-5]|2[0-4]\d|[01]?\d\d?)\.){3}(?:25[0-5]|2[0-4]\d|[01]?\d\d?)$/;

Pattern breakdown (matching 0-255):

25[0-5]- 250-2552[0-4]\d- 200-249[01]?\d\d?- 0-199

ipv4Regex.test('192.168.1.1'); // true

ipv4Regex.test('256.1.1.1'); // false (256 out of range)

ipv4Regex.test('192.168.001.001'); // true (leading zeros allowed)

Performance Optimization

The biggest cause of slow regex is backtracking. Excessive use of greedy quantifiers can cause drastic performance degradation.

Greedy vs Lazy Quantifiers

// Greedy - matches as much as possible

'<div>content</div><div>more</div>'.match(/<div>.*<\/div>/);

// Result: '<div>content</div><div>more</div>' (entire string)

// Lazy - matches minimum needed

'<div>content</div><div>more</div>'.match(/<div>.*?<\/div>/);

// Result: '<div>content</div>' (first only)

Adding ? after a quantifier makes it lazy: *?, +?, ??

Optimization Tips

- Use anchors: Clearly limit scope with

^and$ - Use specific character classes: Use

[^<]*instead of.* - Use non-capturing groups: Use

(?:...)when capture isn't needed

// Capturing group - slower (stores match results)

/(abc)+/

// Non-capturing group - faster (doesn't store)

/(?:abc)+/

Differences by Language

| Feature | JavaScript | Python | Java |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syntax | /pattern/flags | r'pattern' | Pattern.compile("pattern") |

| Unicode | /u flag | Built-in support | Pattern.UNICODE_CASE |

| Named groups | (?<name>...) | (?P<name>...) | (?<name>...) |

| Lookahead | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| Lookbehind | Variable length limited | Supported | Supported |

Using Regular Expressions in JavaScript

const str = 'Contact us at support@example.com or sales@example.com';

const regex = /[\w.-]+@[\w.-]+\.\w+/g;

// Find all matches

const emails = str.match(regex);

// ['support@example.com', 'sales@example.com']

// Replace

const masked = str.replace(regex, '[email hidden]');

// 'Contact us at [email hidden] or [email hidden]'

// Split

'a,b;c:d'.split(/[,;:]/);

// ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

// Iterative matching (matchAll)

for (const match of str.matchAll(/(\w+)@(\w+\.\w+)/g)) {

console.log(`Local: ${match[1]}, Domain: ${match[2]}`);

}

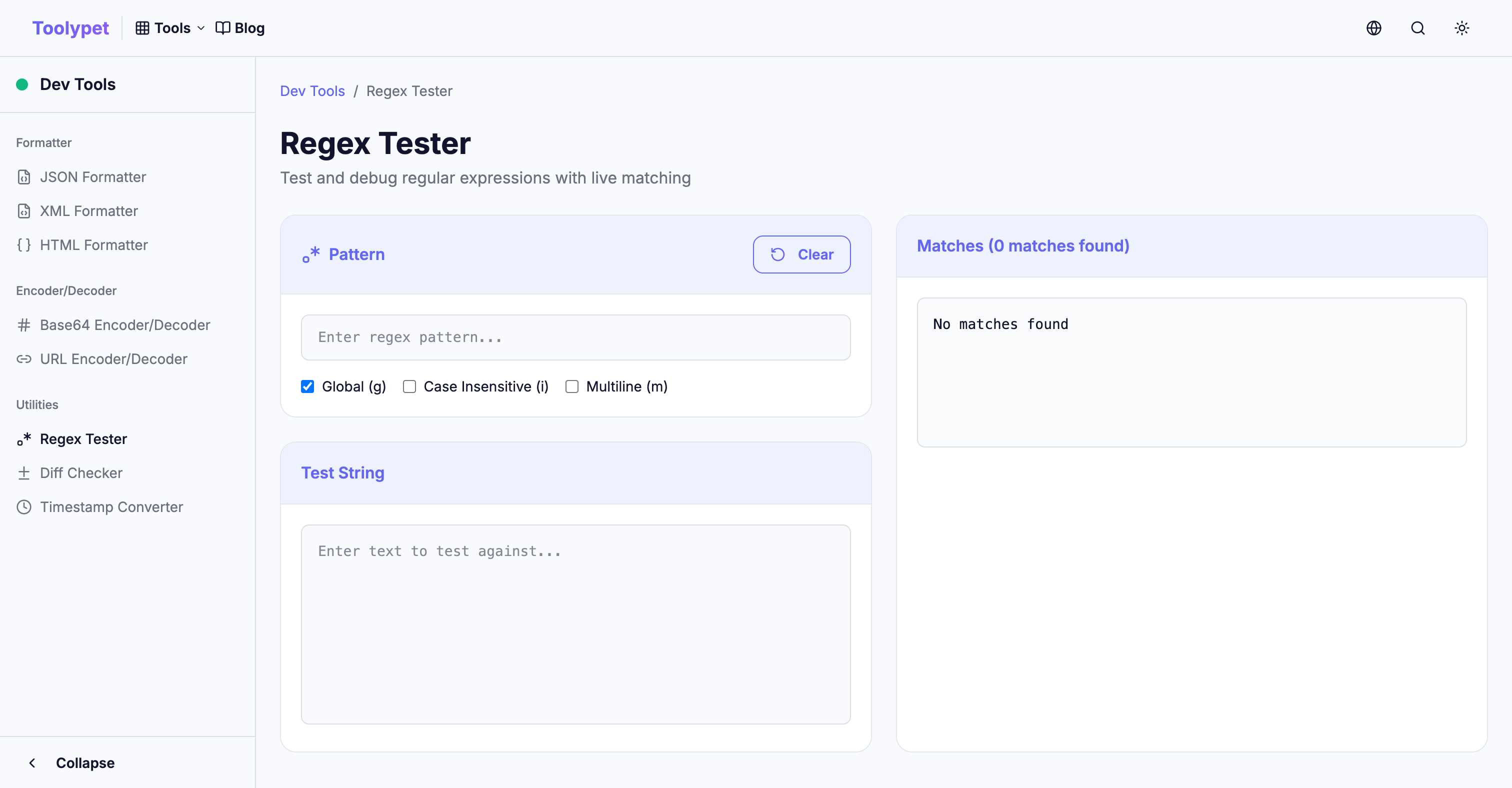

Toolypet Regex Tester

The hardest part of writing regular expressions is getting immediate feedback. Toolypet's Regex Tester solves this problem:

- Enter pattern and test string to see real-time matching results

- Visually displays what each capture group matched

- Easily test multiple flags (g, i, m) with toggles

- Provides frequently used pattern templates

When debugging complex regular expressions, validating in Toolypet first is much more efficient than testing directly in code.